“¿Tu eres Gay?”

Josh Castillo

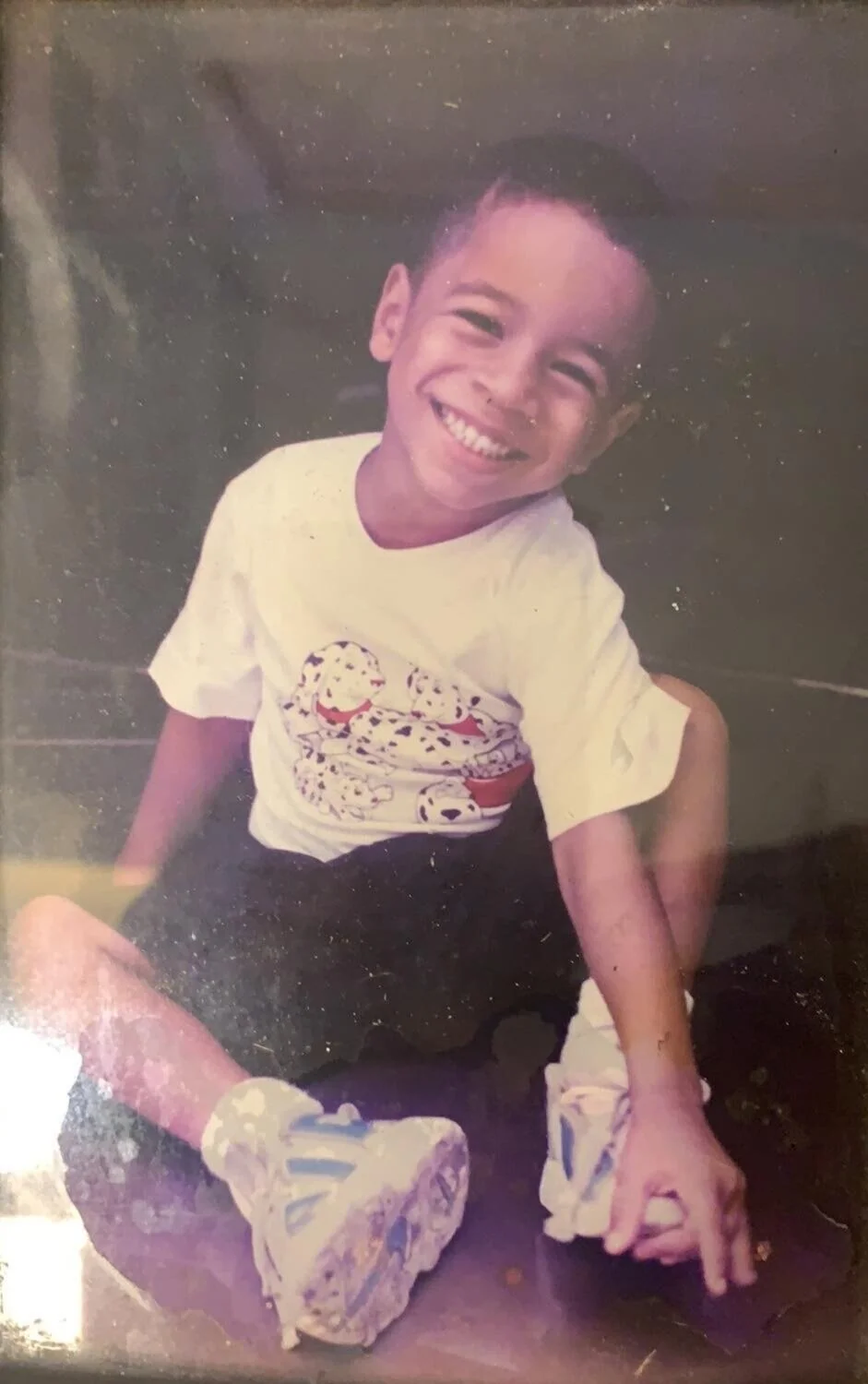

From left to right: the author, his great-grandmother, and Mami.

I always steered toward the heels. Clunky two-inch brown leather heels, next to my grandmother’s bed. Maybe they made me feel powerful. I was smaller than the average kid, and to feel tall was to feel formidable. I’d place them on my feet, stumble along for a bit, trying in earnest to master them. But I never did. To this day, I still stumble in heels.

My mother had me when she was nineteen. Her father believed she wasn’t fit to be a mother. So, a month after I was born, he took me to the Dominican Republic, ostensibly to meet my grandmother. But it wasn’t just a meeting. I wasn’t going back to New York. In that moment, grandma became Mami.

Mami used to take me down to Las Matas de Farfan, a small town on the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, to visit our family. Getting there was a six-hour trek. Along the way, I’d see kids on donkeys heading to market, and merchants selling queso jalao’. Arriving in town, we were treated like royalty. You could hear and feel the music miles away, pounding the pavement. Longaniza and bistec permeated the air. We’d step out of the car to a bombardment of love—a red carpet moment.

“Hola mijo”

“Guao tu si estas grande!”

While my male cousins played tag and wrestled, I gravitated toward the girls. Mami would always tell me, “No te ensucies!” and I obeyed. I never wanted to get my outfits dirty.

The girls were young and didn’t think twice about my mannerisms or my fashion sense. They’d just exclaim, “Ay, que lindo eres.” When the girls and I played house, the adults would see me playing the husband role and use it as an excuse to pin me as someone’s novio. It wasn’t that they were bothered by me—it was more that I was something, somebody, they were unable to recognize.

My male cousins weren’t always as kind. They would tease me for my mannerisms—the way I walked, the sound of my voice. The older men ridiculed me for failing to objectify or throw piropos at women as they passed. Failure to comply meant a barrage of names: un maricón, marica—even pato.

But none of those insults ever came from Mami. No matter how vibrant and flamboyant my outfit was, she’d shield me from negativity. I could walk around proud in my favorite baby-blue denim overalls, my blue button-up and my cowboy hat—all relics of an obsession with Toy Story. When some kid called me out, Mami would clap back.

“Tu quisieras ser como él!”

Eventually, I did return to New York to be with my biological mother. It was a slow process, learning to connect with her, but the division healed. Ultimately, Ma was the first person to whom I came out.

But I know it was Mami that gave me the courage not to fear being myself.

Mami often told me that the moment she held me in her arms it was as if I’d been imprinted on her. Her own children had already grown up, so I was this new challenge for her—a new purpose. In fulfilling that purpose, she made me so comfortable in my own skin that, when I finally came out to her, it was entirely by accident.

I was twenty, standing in Mami’s kitchen in the Heights speaking to my Ma about my boyfriend—in English, so Mami wouldn’t understand. During the conversation, I said the word.

Mami completely dropped everything she was doing and said, in Spanish, “Who’s gay?”

I paused, surprised.

“¿Tu eres gay? Pues mijo, I don’t care!” Then she proceeded with what she was doing as our laughter filled the room.

Joshua Castillo is a Spanish Literature major at Hunter College who wishes to pursue a career in linguistics. He has a deep admiration for choreography (especially K-Pop) and film. His love for his younger niece and cousin fill his life. He lives in Washington Heights, NYC surrounded by his Dominican culture. @josh.jpegs